- As the human life history evolved, a unique kin structure also emerged, leading to changes in population structure that result in the large social networks required for cumulative cultural evolution.

- The long human adult lifespan subsequently led to the unique evolution of a significant post-reproductive lifespan.

- Social interaction networks among humans are tremendously larger than for any other primate.

Highlights

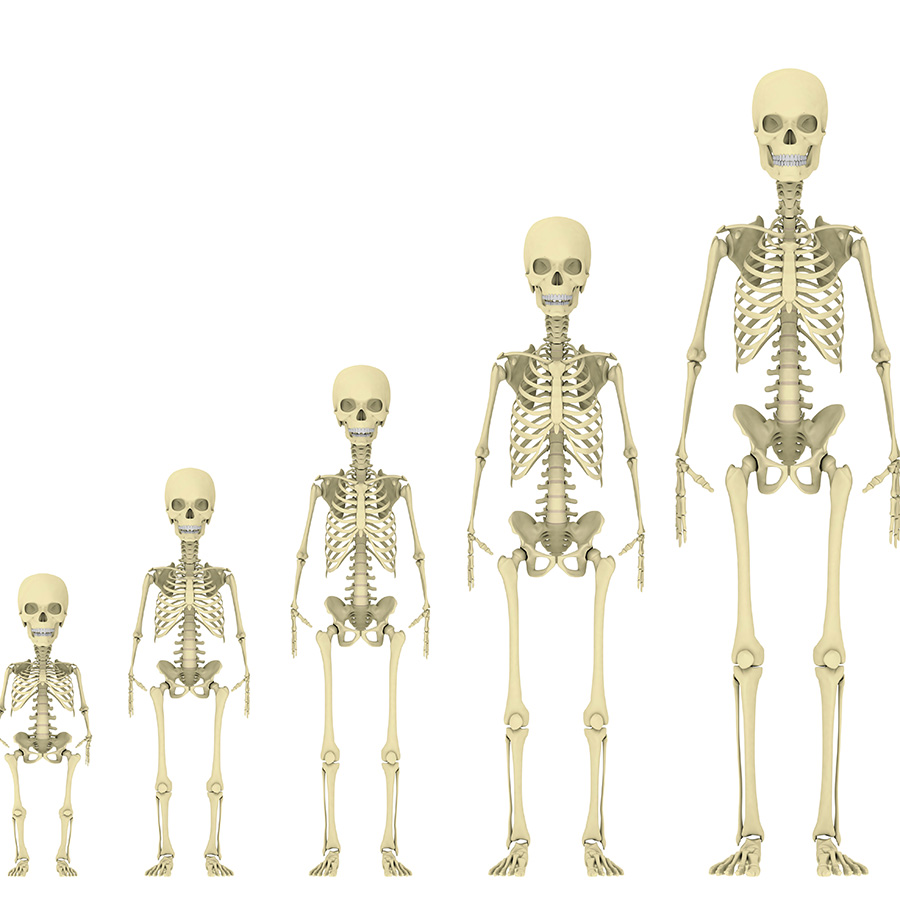

In traditional societies, humans exhibit a series of unique life history traits. Compared to other apes, humans have 1) a longer juvenile period, 2) a longer adult lifespan, 3) high early fertility that ends long before the expected lifespan, and 4) assisted reproduction by post-reproductive adults. These novel traits evolved in conjunction with other adaptations that make our species “obligate cooperative breeders.” This means that pair-bonded reproductive adults require outside help in most human societies. As the human life history evolved, a unique kin structure—which means a system of social relationships connecting people in a culture who are related and includes reciprocal obligations—in combination with increasing prosocial cooperation, also emerged, leading to changes in population structure that result in the large social networks required for cumulative cultural evolution. Prosocial relates to behavior that is positive, helpful, and intended to promote social acceptance and friendship.

It does take a village

First, consider the changes in human life history traits. Humans have longer gestation periods than chimpanzees and show slightly higher birthweight, yet children are weaned at earlier ages than chimpanzees, and then grow at slower rates during much of their long juvenile period. This is almost certainly not strictly due to energy constraints because human children undergo a unique pronounced adolescent growth spurt not seen in other apes without any corresponding increase in their daily food acquisition. If food could have been available for increased child growth all along, why do human children grow at much lower rates than chimpanzees through middle childhood?

Human life history is defined by the growth, developmental, and reproductive events that occur over the course of one’s life.

Image credit Shutterstock

The most obvious hypothesis is that humans delay reaching full adult body size while they instead focus time and energy on brain development and acquiring cultural information that they need adulthood. Indeed, in most societies, children and teens produce very little and peak production generally is not achieved until middle adulthood—more than a decade after reaching full body size.

When all age-specific production is considered, along with mean birth and survivorship rates, and the long juvenile co-residence with parents, it becomes clear that human nuclear families can generally expect periods of time when there are more mouths to feed that can be provisioned given family composition and expected age-specific production rates. For this reason, some researchers have referred to humans as “obligate cooperative breeders.” Typical families must receive food from outside the nuclear family including unmarried adult males, young couples with few children, and post-reproductive women and men. On average there are 1.25 nonreproducing helpers for each breeding pair in the population. In this sense, it really does “take a village to raise a child.”

Social interaction networks among humans are tremendously larger than for any other primate. Due to these large, cooperative interaction networks, social learning became the adaptive niche of our species.

Image credit Shutterstock

The low adult mortality rates, which favor longer childhood and delayed sexual maturity for human children, are probably the result of reduced predation due to culturally acquired weapons, food sharing, and cooperation that ameliorates the dangers of accidents and illness. Humans can recover from serious accidents and poor health, because injured adults are fed and cared for by group co-residents.

This low baseline mortality in ancestral humans (around one-fifth that of wild chimpanzees in early adulthood) also favored the evolution of slower aging. Importantly, the long human adult lifespan subsequently led to the unique evolution of a significant post-reproductive lifespan. In women, this is observed as menopause, while survivorship is still high, and most men do not have any children after their mid-50s. Despite this reproductive cessation, many grandmothers and grandfathers survive into their 70s and more. These post reproductive “grandparents” provide critical resources, services, and knowledge that allow for earlier reproduction and high fertility among young adult sons and daughters.

A unique social mating system

The human monogamous mating system is also unique among apes. Although males sometimes pair-bond with more than one female simultaneously, humans generally form long-term pair-bonded relationships. Empirical studies in traditional societies suggest that even when polygyny is socially acceptable, fewer than 5% of men have more than one wife.

This mating system has produced a unique social system. First, children usually spend an extended juvenile period with their father and full siblings where they learn that fathers invest heavily in offspring. This may explain why humans are the only animal on Earth that recognizes and preferentially cooperates with “affinal” kin, meaning that brother-in-law, sister-in-law, father-in-law, mother-in-law, son-in-law, and daughter-in-law are all recognized via long-term associations (pair bonding), and they are known to invest in shared close kin. Shared nieces and nephews, grandchildren, and cousins means that genetically unrelated individuals still have strong shared genetic interests. Humans alone recognize those common genetic interests and behave preferentially towards affinal kin.

The ease and frequency of movement between human communities is exceptional compared to any other primate. Parents visit their adult offspring and vice versa. Adult brothers and sisters visit each other regularly and often transfer social groups in order to co-reside through the adult lifespan.

Image credit Shutterstock

Are you my brother?

All this means that that adolescent dispersal results in well-known and emotionally bonded kin living in nearby social groups, and as a result, the nature of relationships between members of different social groups in humans is unique among the primates. When members of two chimpanzee communities meet, there is open hostility. Males do not necessarily know their half-sisters, who might not have shared any significant childhood co-association with them. And male chimpanzees have no reason to cooperate with males from another community, who might occasionally mate with their sisters but provide no investment to their sister’s offspring. Chimpanzee males from other communities are competitors and enemies to be killed or to be avoided.

Humans recognize emigrant siblings because they are likely to have shared long juvenile periods together with the same parents. Human males recognize that their sister or daughter is pair bonded to a long-term mate who invests significantly in provisioning and caring for their sister’s or daughter’s offspring. Thus, when a human male meets a male from another “community,” he must immediately consider that the new male might potentially be: 1) his daughter’s mate, 2) his sister’s mate, 3) his daughter or sister’s son, or 4) a close male relative of his daughter’s or sister’s mate. All those individuals have strong shared genetic interests with males in neighboring groups, and they are expected to invest in children who are closely related to the males in neighboring groups. The result is that friendly interactions and visiting are far more likely with the human reproductive and mating system. Indeed, researchers have shown empirically, using data from more than 30 hunter-gatherer societies, that intergroup visiting and residential transfers are extremely common.

The social network

The ease and frequency of movement between human communities is exceptional compared to any other primate. Parents visit their adult offspring and vice versa. Adult brothers and sisters visit each other regularly and often transfer social groups in order to co-reside through the adult lifespan.

This leads to another exceptional trait of human social structure. Social interaction networks among humans are tremendously larger than for any other primate. Due to these large, cooperative interaction networks, social learning became the adaptive niche of our species. Work with hunter-gatherers suggests that ancestral humans directly observed and interacted with around 15 times more adults in a lifetime, on average, than do wild chimpanzees. This allowed for the introduction of novel ideas, technology, and techniques that ultimately facilitated cumulative cultural evolution in humans but not in other apes.

Not only has this resulted in the spectacular biological dominance of our species and technological complexity that is unparalleled among life forms on earth, but it has also led to even greater levels of cooperation in human societies via culturally transmitted social norms that rapidly spread according to their effects on the relative well-being of different cultural populations. In this way humans became a uniquely unique species, an outlier among the nine-million life forms currently inhabiting the planet.

Written by Kim Hill PhD