- Cognition, culture, and cooperation explain the unusual features of our species and these features coevolved with our unusual life history and population structure.

- Today people cooperate on vast scales to dominate the world’s ecosystems like no other species in the history of life.

Highlights

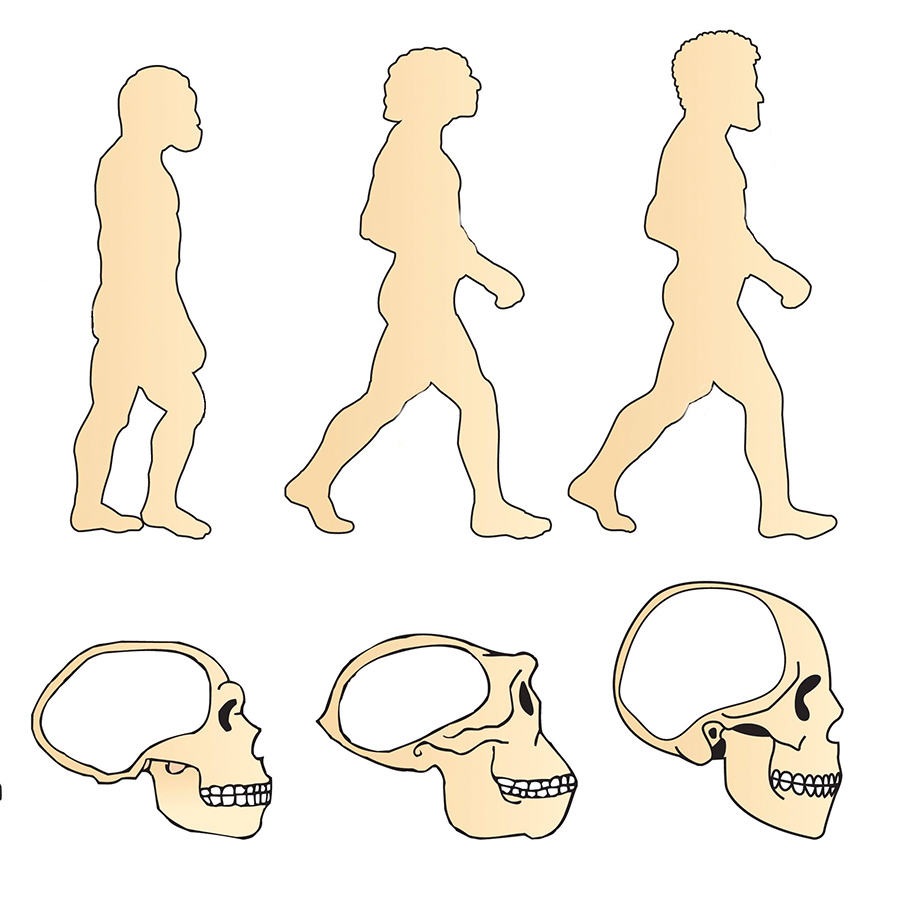

Humans are a unique species

Humans are a unique species. Six million years ago, our ancestors were much like other apes. They lived in a modest range of African habitats, lived in small groups, and made simple tools. By 10,000 years ago, our species was an outlier in the natural world. Our geographic and ecological ranges are larger than that of any other terrestrial mammal. Modern humans left Africa about 60,000 years ago and proceeded to occupy every terrestrial habitat on Earth except Antarctica and a few remote islands. Human biomass is eight times the biomass of all other wild terrestrial vertebrates combined. Today people cooperate on vast scales to dominate the world’s ecosystems like no other species in the history of life.

Evolution has been creating vertebrate species for about 350 million years, and we are outliers in comparison with every single one of them.

Image credit Shutterstock

This leads to the obvious question, why are we such unusual animals? People often say that asking this question is just vanity, and there is some truth to this. Most of us are more interested in our own evolution than in the evolution of barnacles or baboons. But it isn’t just vanity. Evolution has been creating vertebrate species for about 350 million years, and we are outliers in comparison with every single one of them.

Something very unusual happened during the Pleistocene (around 2.58 million years ago to 11,700 years ago) evolution of our species, and it’s of great scientific interest to know what it was. This question gets its bite from the certainty that humans are the products of organic evolution, just like every other species. Before Darwin, the explanation for human uniqueness was obvious—we were nearer to angels than to animals. After Darwin, the puzzle was real. So, what happened?

We are smarter than other animals

One obvious factor is that we are smarter than other animals. Beginning about 3.0 million years ago, brain sizes in the hominin lineage began to increase, and by 500,000 years ago, hominin encephalization (brain growth) was greater than all other mammals.

Beginning about 3.0 million years ago, brain sizes in the hominin lineage began to increase, and by 500,000 years ago, hominin encephalization (brain growth) was greater than all other mammals.

Image credit Shutterstock

There is evidence that humans are better at causal reasoning than other species, and this enables us to adjust our behavior in response to new environments. This leads to better tools and more productive subsistence techniques allowing us to survive in a wider range of environments. We also seem to be better at “theory of mind” than other species, and it is plausible that this enables us to negotiate more complex, mutually beneficial social arrangements. These cognitive abilities allow us to flexibly adapt to novel circumstances better than other species. Increased intelligence is a key innovation that has made Homo sapiens different from other creatures.

Humans adapt culturally

A second important factor is that, unlike other species, humans adapt culturally. It is clear that greater intelligence alone isn’t the answer. Even in the simplest foraging societies people depend on tools, foraging techniques, and ecological knowledge that no individual could invent on their own. Individuals do not solve most of the problems they need to solve. Instead, human populations accumulate solutions, and our exceptional social learning abilities allow these solutions to spread from one individual to another. Sometimes cultural adaptation does involve conscious design based on our sophisticated cognition, but often it does not. Culture is important part of the explanation for human uniqueness because it permits the gradual accumulation of adaptations without causal understanding, adaptations that were not intelligently designed and no individual in the population understands.

And humans are more cooperative

Third, humans are much more cooperative than other mammals. In every human society people cooperate with many unrelated individuals. Division of labor, trade, and large-scale collective action are common. The sick, hungry, and disabled are cared for, and social life is regulated by commonly held moral systems enforced, albeit imperfectly, by third-party sanctions. In contrast, in other mammal species, cooperation is limited to relatives and small groups of reciprocators. There is little division of labor or trade, and no large-scale collective action. No one cares for the sick or feeds the hungry or disabled. The strong take from the weak without fear of sanctions by third parties. The behavior of other vertebrates is easy to understand. Natural selection only favors individually costly, prosocial behavior when the beneficiaries of the behavior are closely related, and the mammalian reproductive biology severely limits the number of close relatives an individual can have. The scale and intensity of human cooperation results from novel evolutionary mechanisms that depend on the novel features of human biology—greater intelligence, cultural adaptation, and combinatorial language.

In every human society people cooperate with many unrelated individuals. Division of labor, trade, and large-scale collective action are common.

Image credit Shutterstock

Enhanced cognition, cultural adaptation, and intensive cooperation coevolved with a number of important, derived aspects of human life-history and population structure. Compared to other primates, humans develop slowly reaching sexual maturity at a later age and live a long time. However, they also have much shorter interbirth intervals than other primates of comparable size. This unusual combination is likely due to the cooperative nature of forager groups in which there are extensive food transfers to reproducing women. Humans are also unusual in that there is extensive contact, friendly relations, and sometimes cooperation between individuals living in different residential groups.

Humans are unusual because there is extensive contact, friendly relations, and sometimes cooperation between individuals living in different residential groups.

Image credit Shutterstock

This is likely related to pair-bonding within groups and the cognitive capacity to keep track of relatives by marriage in other groups. Finally, human populations are organized into culturally-related, often linguistically marked, groupings that are much larger than residential groups, and these groups play an important role in large-scale cooperation and conflict. In sum, cognition, culture, and cooperation explain the unusual features of our species and these features coevolved with our unusual life history and population structure.

Written by Rob Boyd PhD, Sarah Mathew PhD, Thomas Morgan PhD