- Unlike other organisms, humans rely on culturally acquired information, and it is the ability to make use of culturally acquired information that has made our species such a spectacular evolutionary success.

- Only humans acquire a wide range of adaptive knowledge that has accumulated over time.

- The importance of culture in human affairs has led many anthropologists to conclude that evolutionary thinking has little to contribute to understanding human behavior

- Humans cannot be understood without the complex interplay between biology and culture because cumulative cultural evolution is rooted in a novel evolutionary trade-off between benefits and costs.

- Human social learning mechanisms are beneficial because they allow humans to accumulate vast reservoirs of adaptive information over many generations, leading to the cumulative cultural evolution of highly adaptive behaviors and technology.

Highlights

Living in a world of supermarkets and central heating makes it easy to underestimate the difficulty and problems of human foragers to adapt to environments all over the world.

Complexity of adaptations

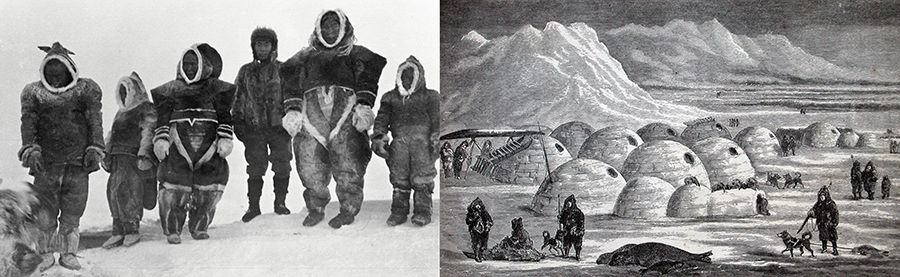

To get a feeling for the complexity of such adaptations, here is an example. Until less than 100 years ago, the Central Inuit lived by hunting and fishing on Canada’s northern coast. They depended on a tool kit crammed with complex, highly refined, and well-designed implements. They made cleverly designed clothes, mainly from caribou skins that were both light and warm. This required a host of complex skills, curing hides, spinning thread, making needles, and stitching well-fitting garments. The Central Inuit depended on many other cleverly designed tools—soapstone lamps to light their snow houses, cook their food, and melt ice for drinking water; kayaks and multipiece toggle harpoons for seal hunting; and sophisticated composite bows for hunting caribou. They also depended on a vast amount of local knowledge, the habits of the animals, how to move on ice, how to judge the weather, and where food can be found as the seasons change. The list is very long.

The Central Inuit made on cleverly designed caribou fur clothing that allowed them to live in Arctic environments that averaged well below freezing in the winter. They lived in sizable villages on the sea ice during the winter sealing season. Snow houses, dog sleds, and kayaks were essential for their subsistence.

Image credit: left; right

Culturally acquired information

Individuals aren’t nearly smart enough to acquire all of this knowledge in a single lifetime without any help from others. But, this is exactly what other animals learn do—they rely mainly on information encoded in their genes and individual experience to figure out how to find food, make shelter, and make tools. This isn’t even close to plausible for the complex tools that people rely on. Kayaks, bows, and dogsleds are complicated artifacts with multiple interacting parts made of many materials. Working out the best design or even a workable design for something like this from scratch is very hard to do. The Inuit could make the tools that they needed and master all the tasks that they needed to stay alive in the Arctic because they could draw on a vast pool of information that was known by other people in their population. They could gain access to this information by watching others, asking questions, or being taught. That is, unlike other organisms, humans rely on culturally acquired information, and it is the ability to make use of culturally acquired information that has made our species such a spectacular evolutionary success.

Culture is common among other animals, but cumulative cultural evolution is rare. Biologists documented a great deal of behavioral variation across groups in various species, most notably chimpanzees, orangutans, and capuchins. For example, chimpanzees living on the western shores of Lake Tanganyika raise their arms and clasp hands while they groom, but chimpanzees living on the eastern shore of the lake don’t do this.

Chimpanzees in the Gombe forest area will clasp their hands above their head during grooming—but chimpanzees on the other side of Lake Tanganyika do not show this behavior.

Image credit Ian Gilby

Orangutans in some areas use sticks to pry seeds out of fruits, but orangutans at other sites have not mastered this technique and cannot extract the seeds. There are also examples of cultural traditions in a variety of species outside the primates, such as fish, birds, cetaceans, meerkats, and rodents. These traditions encompass a diverse array of ecologically significant behaviors, including food preferences, foraging techniques, and alarm calls. But in other animals, there are very few examples of cumulative cultural evolution, and in every case, it is limited to a single domain, like song dialect or migration route, and other behaviors are not culturally transmitted. Only humans acquire a wide range of adaptive knowledge that has accumulated over time.

Cumulative cultural evolution

There are three reasons that cumulative cultural evolution create adaptations that are beyond the inventive capacity of individuals.

First, cultural learning can allow individuals to learn selectively. This is advantageous because opportunities to learn from experience or by observation of the world vary. For example, a rare, accidental event could provide evidence that heating some kinds of stone to the right temperature makes it much easier to knap or flake pieces to shape a blade. Such rare cues allow accurate low-cost inferences about the environment. However, most individuals won’t observe these cues and thus making the same inference will be much more difficult for them. Organisms that can’t imitate must rely on individual learning, even when it is difficult and error prone. Each individual has to independently discover that heating stone makes it easier to knap.

In contrast, an organism capable of cultural learning has options, copying when she has little reliable information, but learning individually when it’s cheap and accurate. Research has shown that selection can lead to a psychology that causes most individuals to rely on cultural learning most of the time and also simultaneously increase the average fitness of the population over the fitness of a population that does not rely on cultural information.

Second, cultural learning is advantageous because it allows acquired improvements to accumulate from one generation to the next. Many kinds of traits admit successive improvements toward some optimum. Bows vary in many dimensions that affect performance—such as length, width, cross section, taper, and degree of recurve. It is typically more difficult to make large improvements by trial and error than small ones. Thus, it is much harder to design a useful bow from scratch than to tinker with the dimensions of a reasonably good bow. A cultural learner can take advantage of the accumulated history of small improvements, while an individual learner has to start from scratch. Recently, researchers have shown that Hadza hunter-gatherers in northern Tanzania depend on excellent bows whose design they do not fully understand.

The Hadza of Tanzania use powerful, well-designed bows to hunt large game. Research suggests that they are able to does this without a causal understanding of some aspects of bow mechanics.

Image credit Shutterstock (left); Jacob Harris (right)

Finally, if learners can compare the success of individuals modeling different behaviors, then a propensity to imitate the successful can lead to the spread of traits that are correlated with success even though imitators have no causal understanding of the connection. You see that your uncle’s bow shoots farther than yours and notice that it is thicker, but less tapered, and uses a different plait for attaching the sinew. You copy all three traits, even though in reality, it was just the plaiting that made the difference. As long as there is a reliable statistical correlation between plaiting and power, the plaiting form trait will change so as to increase power. Causal understanding is helpful because it helps to exclude irrelevant traits like the color the bow is painted. However, causal understanding need not be very precise as long as the correlation is reliable. Copying irrelevant traits like thickness or color will only add noise to the process.

Culture in human affairs

The mechanisms that allow the cumulative cultural adaptation of such complex adaptation also sometimes leads to evolutionary outcomes not predicted by ordinary evolutionary theory. The importance of culture in human affairs has led many anthropologists to conclude that evolutionary thinking has little to contribute to understanding human behavior. They argue that evolution shapes genetically determined behaviors but not behaviors that are learned, and so culture is independent of biology. Many evolutionists have made the opposite mistake. They reject the idea that culture makes any fundamental difference in the way that evolution has shaped human behavior and psychology. If natural selection shaped the genes underlying the psychological machinery that gives rise to human behavior, the machinery must have led to fitness-enhancing behavior, at least in ancestral environments. If the adaptation doesn’t enhance fitness in modern environments, that’s because our evolved psychology is designed for life in a different kind of world.

Both sides in this argument have got it wrong. Humans cannot be understood without the complex interplay between biology and culture because cumulative cultural evolution is rooted in a novel evolutionary trade-off between benefits and costs. Human social learning mechanisms are beneficial because they allow humans to accumulate vast reservoirs of adaptive information over many generations, leading to the cumulative cultural evolution of highly adaptive behaviors and technology. Because this process is much faster than genetic evolution, it allows human populations to develop cultural adaptations to local environments: kayaks in the Arctic and blowguns in the Amazon.

The process of building a boat that will float without tipping over, stay watertight, and last a long time, is an example of cultural knowledge—individuals aren’t nearly smart enough to acquire all of this knowledge in a single lifetime without any help from others.

Image credit Kim Hill (right and right), Benjamin Trumble (middle)

The cost of social learning

The ability to adjust rapidly to local conditions was highly adaptive for early humans because the Pleistocene was a time of extremely rapid fluctuations in world climates. However, the psychological mechanisms that create this benefit come with a built-in cost. Remember that the advantage of learning from others is that it avoids the need for everyone to figure out everything for themselves. We can simply do what others do. But to get the benefits of social learning, people have to be credulous, generally accepting that other people are doing things in a sensible and proper way. This means that people’s behavior in a wide range of domains, including such areas like subsistence and technology, is better predicted by what language they speak than what kind of environment they live in.

This credulity helps populations accumulate hard-to-understand adaptations, but it also makes us vulnerable to the spread of maladaptive beliefs and behaviors. If everyone in our community believes that it’s beneficial to bleed sick people or that it’s a good idea to boil polluted water before drinking, we believe that, too. This is how we get wondrous adaptations such as kayaks and blowguns. But we have little protection against the perpetuation of maladaptations that somehow arise. Even though the capacities that give rise to culture and shape its content must be (or at least must have been) adaptive on average, the behavior observed in any particular society at any particular time may reflect evolved maladaptations.

Written by Rob Boyd PhD