Modern humans are reasonably unique among mammals in that they regularly prey on other animals far larger than them. Humans do this by using advanced weapons (projectiles, poisons, traps, etc.) to kill these large and dangerous prey. Because of this ability, many hunter-gatherer groups have diets where animal foods are a common, even predominant, component of the diet, and this again is unique among primates. We call this the “human predatory pattern,” or HPP for short. For this reason, the origins and evolution of the human predatory pattern has been a central research question for paleoanthropologists since its inception.

Meat is a high-quality resource due to its rich protein levels and many important nutrients. Modern taphonomic studies, which deal with the processes of fossilization, show us that there is one best way to attain meat in the wild and that is to be the killer of an animal. Animals that are killed are rapidly stripped of their flesh, so it is hard to attain lots of meat by being second in line (a scavenger), unless you can drive lions and hyena off their prey. Exceptions to this would be the death of very large prey, such as elephants, and there is good evidence that sabertooth cats, which were present at this time, focused predation on large prey.

Paleoanthropologists have long theorized that a key milestone in becoming human was when hominins began eating meat, and thus to get regular access to that meat, we think they must have been hunters. Since the brain is such a hungry organ and requires a lot of protein, many paleoanthropologists thought that the expansion of brain size and meat eating were inextricably linked. Since the oldest Oldowan tools date to 2.5 million years ago, close to the origin point of early Homo and the first evidence for brain expansion, paleoanthropologists thought for many years that these illustrated an evolutionary link—tools and meat and brains! But does it?

Recently, scientists have dissected this tools-meat-brain hypothesis. They point out that mammals have other equally important food types in their carcass, for example fat, which is rich in calories and mostly found within the bones in the form of marrow. To access this marrow, one either needs really strong jaws and big crushing teeth (like a hyena) or a hammerstone and the ability to hold that hammerstone and pound it on things (Lucy certainly had that ability). Importantly, African predators like lions and leopards have limited abilities to break open bones—they leave these for the bone crackers the hyenas or a hominin with a hammerstone. Hominins could get animal fats without being a hunter. Animal carcasses are a rich package of high-quality food, but researchers argue that it is better to think of these two foods, meat and marrow, as separate, and their addition to the hominin diet over time as staggered. Let’s do that.

Our ape cousins, the chimpanzees, have an eclectic diet that, while based in plants, includes substantial amounts of meat. Chimpanzees are well known to kill and eat small antelope and monkeys. This has led paleoanthropologists to theorize that the last shared common ancestor of chimps and hominins also ate some meat from small mammals and over time as hominins evolved separately from the chimpanzee lineage, they slowly evolved this pattern up to hunting and killing large mammals like wildebeest and buffalo. We can call this the “chimpanzee model” for the origins of the HPP. Researchers showed that this model has numerous flaws and no longer fits the evidence. They offer a new model that argues for this series of steps:

- use of pounding tools all the way back to the shared common ancestor

- movement onto more open habitats with the origins of bipedality and the expansion of these habitats

- encounters with bones remaining from the kills of other carnivores

- bashing of bones with pounding tools to access marrow (percussive scavenging)

- modest occasional scraping of bits of flesh from these bones

- beginnings of stone tool flaking to improve the ability to butcher meat and disarticulate bones

- incremental hunting of animals and their butchery with these flaked tools.

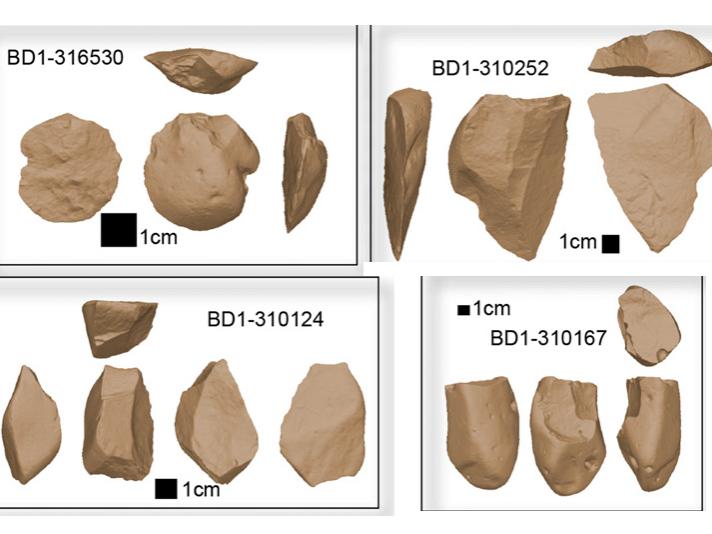

How does this square with the evidence? The Dikika evidence along with the tool-using hand of Australopithecus afarensis are consistent with this new model. Several Oldowan-age archaeological sites have comingled stone tools and substantial numbers of fossil ungulates bones with stone tool cut marks and hammerstone percussion marks that broke open the bones. But scientists disagree as to whether these remains signal persistent active hunting or scavenging. More data and research are required. But at this stage we can say with confidence that during the Oldowan, hominins were making stone tools, using hammerstones to bash open bones for marrow, stripping at least small amounts of meat off bones, and maybe even feasting off whole carcasses. While there is little evidence, other forms of evidence such as isotopes show us that these hominis were eating large amounts of plant foods, but there is debate over exactly what these plants foods were.

Written by Curtis Marean PhD