- Lomekwi and Dikika data indicate that at least one hominin species, living during the same time of Lucy, was breaking stones to use as tools and using sharp stone edges as knives to butcher animals

- Earlier hominins were not thought to have the cognitive skills or dexterity to create tools from stone. The Lomekwi and Dikika evidence have scientists taking a new look at the origins of these behaviors.

Highlights

Archaeological evidence in the form of stone tools from Lomekwi, Kenya, and butchered animal fossils from Dikika, Ethopia, indicates that our hominin ancestors were creating and using stone tools more than three million years ago, long before the emergence of our genus, Homo. The Lomekwi and Dikika data indicate that at least one hominin species, living during the same time of Lucy, was breaking stones to use as tools and using sharp stone edges as knives to butcher animals. Before these discoveries, the earliest evidence for tool use was ascribed to the origins of Homo. The behaviors of toolmaking and meat eating were thought to be unique to Homo, arising from a cognitive leap that differentiated our genus. Earlier hominins, such as Australopithecus, the genus thought to be the ancestor of Homo, were not thought to have the cognitive skills or dexterity to create tools from stone. The Lomekwi and Dikika evidence have scientists taking a new look at the origins of these behaviors.

Lomekwi technology

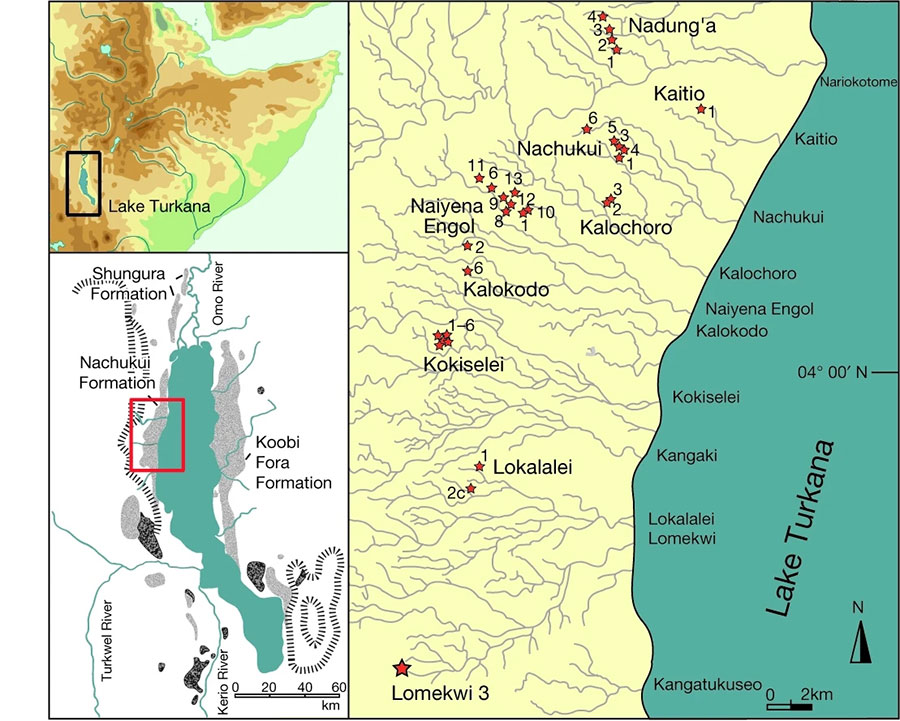

The Lomekwi artifacts were first discovered eroding out of a dry riverbed near the shores of Lake Turkana in Kenya. Further excavation yielded more stone tools, and the sediments surrounding the tools, allowed for the artifacts to be dated to around 3.3 million years ago. This makes them the oldest stone tools yet discovered, predating the earlier technology called the Oldowan industry, by about 700,000 years ago.

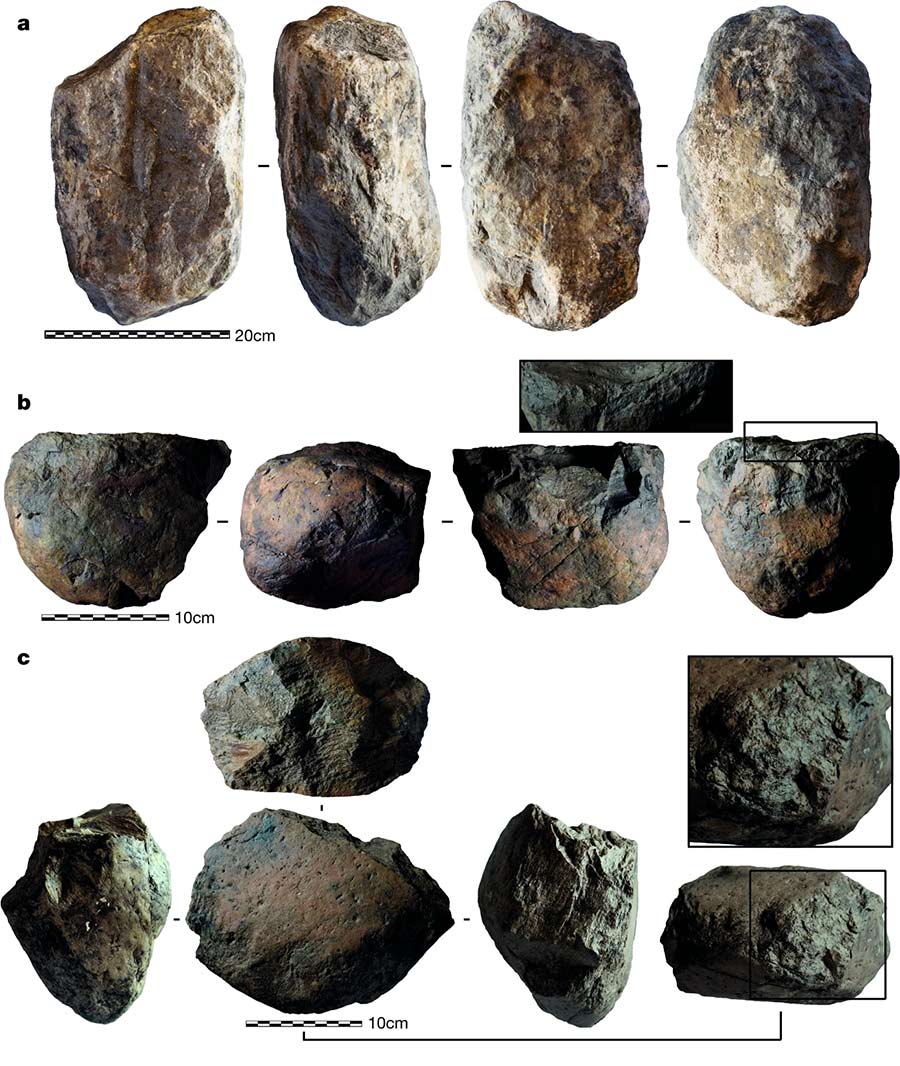

3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya. Image credit Harmand et al. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature14464

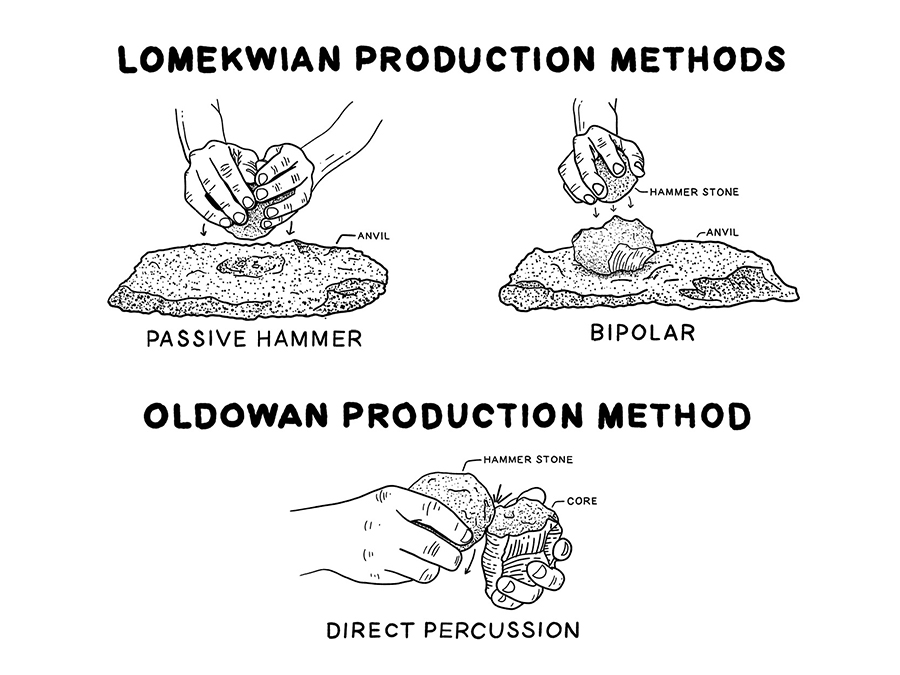

These stone artifacts show clear evidence of intentional breakage. Experiments aimed at re-creating these tool forms suggest that these tools were created by placing one stone on a flat rock and striking it with a hammer stone, similar to a hammer and anvil technique. Another possible method could be tightly holding a rock with both hands and bashing it against a hard anvil rock to break it. This method for chipping stone is simpler than how Oldowan tools were made, which involved holding a stone in one hand and carefully chipping away at it by hitting the surface at just the right angle with a second stone. The method used to make Oldowan tools involves more dexterity and a more complex understanding of how stones break. Oldowan tool production is thought to have emerged in Homo habilis or other early members of our genus. These production differences led the Lomekwi researchers to conclude that the three-million-year-old artifacts belonged to a unique culture they termed the Lomekwian.

Image credit Patrick Fahey

The identity of the maker of the Lomewki tools is unknown. Suspects include Australopithecus afarensis, widely known from the fossil skeleton Lucy; Kenyanthropus platyops, a species known to have lived in the region at this time; or some undiscovered species. What these tools were used for also remains unknown, although they could have been used in nut cracking or some other form of food processing. The bigger tools in the collection, the largest weighing over 30 pounds, could have functioned as anvils in nut cracking, while smaller cobbles could have been hand-held tools used for bashing and crushing. Sharper stone flakes may have been used for cutting plants or meat.

Geographic location of the Lomekwi 3 site. Image credit Harmand et al. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature14464

Dikika technology

The earliest evidence for meat eating amongst our hominin ancestors come from around 3.4 million years ago, slightly older than the Lomekwi artifacts. Fossil limb bones, likely belonging to antelopes the size of goats and cows were discovered at Dikika, Ethopia, and showed evidence of butchery. The surface of two bone fragments exhibited cut marks made from a sharp stone blade. There was also evidence of percussion marks created when limb bones are smashed to access the bone marrow rich cavities inside. This evidence is the first indication that species in our lineage began to consume animals and were using stone tools to do so. It is possible that the hominin scavenged this meal from another predator rather than hunting itself. While no stone tools have been discovered in association with the cut marks, they could have been made from a naturally sharp stone that was found and collected by a hominin. Stone tools like those found at Lomekwi may also be responsible, but such artifacts have not yet been discovered at Dikika.

Two parallel marks, consistent with stone-tool cutmarks, on a 3.4-million-year-old bone, suggest that hominins may have been butchering animals before the evolution of the first Homo species. Image credit Dikika Research Project

Did Lucy use stone tools?

Like the Lomekwi tools, what species made the Dikika marks is currently unknown. However, the contemporaneous and almost complete fossil skeleton of a juvenile Australopithecus afarensis were discovered not far from where the cut marks were found. Whoever the culprit, the discovery of these cut marks suggests that species in our lineage were consuming meat long before our genus emerged, challenging previous assumptions about the antiquity of hominin meat eating.

Both the Lomekwi artifacts and the Dikika cut marks are the subject of debate amongst paleoanthropological researchers, some of whom doubt the age or validity of the evidence. Some scientists believe that the marks on the Dikika fossil could have been created from trampling of the bone against rough stone or from crocodile teeth, which have been shown to create similar marks on bone. Methods are being developed to use sophisticated models and machine learning to identify the agent that created the Dikika marks rather than relying solely on identification by experts. Further excavations may reveal more evidence for contemporaneous stone tools and fossils displaying butchery marks, which would add further information on the prevalence and function of the stone tool making and meat consumption behaviors of our ancestors three million years ago.

Written by Patrick Fahey