- The study of ancient disease, broadly, is called paleopathology. Paleogenetics is the study of preserved ancient genetic material. Paleopathologists examine ancient and historic humans in order to learn what diseases were present in the past.

- Anthropologists are interested in understanding human evolution, and disease has played a sizeable role in shaping our species.

- If we want to understand human evolution, it is important to consider diseases that were impacting our ancestors long before written language.

Highlights

Humans, like other animals, often get sick. There are a variety of ways that people can get sick, and the resultant conditions are referred to as diseases. Some diseases are communicable (or infectious) and can be passed from one sick individual to another. Communicable diseases are caused when someone is infected with a pathogen (such as a bacteria or virus). As these pathogens grow and reproduce, the infected person becomes ill. There are hundreds of bacterial and viral species that cause disease today. Other diseases are noncommunicable and cannot be passed from person to person; examples of noncommunicable diseases include autoimmune disorders, cardiac disease, and most cancers.

Ancient pandemics

Anthropologists are interested in understanding human evolution, and disease has played a sizeable role in shaping our species. The Black Death, also known as the Plague, is well known as the deadliest pandemic in recorded human history and is estimated to have killed between 30 and 60 percent of Europeans in the 1300s. This dramatically shaped the cultural environment of affected populations, resulting in changes to values, norms, and social structures. In addition to cultural change, the Plague impacted Europeans on a biological level, shaping their evolutionary history. People of European descent are more likely than other populations to have immune system gene variants useful for fighting infection with Yersinia pestis, the bacteria responsible for plague.

Scientists studying the Black Death pulled DNA from bones buried in London’s East Smithfield Cemetery.

Image credit Museum of London Archaeology

Of course, disease is not a new phenomenon, in fact, it predates humans by millions of years. Humans and their earliest ancestors lived (and died) through population-shaping epidemics and contended with many noncommunicable diseases as well. In the case of The Black Death, we have written records of the pandemic, such as descriptions of the disease from physicians. These sources provide historians and scientists with important clues regarding the evolution of disease. By comparing historic descriptions of a condition with modern medical knowledge they can hypothesize how it has changed over time. But what about older diseases? If we want to understand human evolution, it is important to consider diseases that were impacting our ancestors long before written language.

Paleopathology

The study of ancient disease, broadly, is called paleopathology. Paleopathologists examine ancient and historic humans in order to learn what diseases were present in the past. Bones are the most likely part of the body to preserve, and so paleopathological studies generally focus on the skeleton, but sometimes look at mummies, hair, and even preserved feces (coprolites). Some diseases can leave identifying marks (or lesions) on the skeleton during infection, and these lesions are often used to diagnose disease in the skeletal record. By studying these signatures, we learn about patterns of disease in ancient populations and answer questions such as— Where were certain diseases found? How frequently does a specific disease occur? What percentage of a population is affected by the disease?

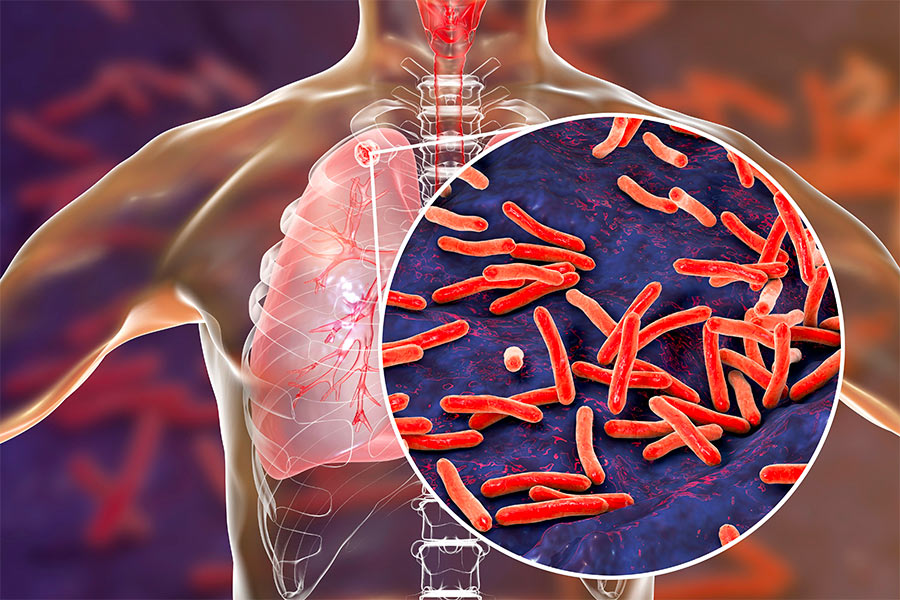

The earliest skeletal evidence of tuberculosis and Chagas’ disease was around 9,000 years ago.

Image credit Shutterstock

Paleogenetics

Recent advances in the field of genetics now allow us to study infectious diseases by extracting the pathogen’s DNA from the (usually skeletal) remains of previously infected humans (and other animals). Paleogenetics is the study of preserved ancient genetic material. Ancient genomes have been sequenced from many extinct organisms, including wooly mammoths, ancient horses, and even Neandertals. DNA degrades over time, breaking into smaller fragments, but can often preserve for thousands of years given the correct environmental conditions (i.e., cold weather, low moisture). In some cases, a small amount of pathogen DNA will be preserved along with the endogenous (belonging to the organism) DNA. Now, the genomes from many ancient pathogens have been sequenced, including those that cause plague, syphilis, tuberculosis, leprosy, salmonella, and others, paving a new road for infectious disease research.

A researcher examines a jaw with teeth in the ancient DNA lab. The lab must maintain a clean room environment so that only the ancient DNA is uncontaminated by any other DNA source.

Image credit Andrew Ozga

Comparison of ancient pathogen genomes to their modern descendants reveals how the organism has changed over time, providing insight into their evolutionary past and clues about how they will continue to evolve today. In the same way that human evolution is impacted by pathogens (and the diseases they cause), pathogen evolution is impacted by humans. When humans and human ancestors migrated around the globe, they brought their pathogens along, creating new distributions of diseases. Human cultural practices, such as sharing of eating or drinking vessels, frequency of group gatherings, and even methods of medical treatment shape the pathogen’s evolutionary environment and the selective pressures it must face.

Ancient genomic studies of Y. pestis reveal how this disease shaped the genome of Europeans during the Black Death. Researchers found that humans have likely hosted the plague pathogen since at least the Late Neolithic period and that they carried it across the European continent via human networks. In many ways, the story of human evolution is intimately connected to the evolution of pathogens. They act as our constant and unsolicited companions. Many are never noticed, and yet they have (and continue to) shape our species.

Written by Stevie Winingear