- Ancient DNA data helps researchers address questions in anthropology, evolutionary biology, and the environmental and archaeological sciences.

- The first Neandertal mitochondrial DNA was recovered in 1997.

- DNA research has identified new branches of the human family tree with minimal fossil evidence like the Denisovans, close relatives of Neandertals.

Highlights

New Paths to Ancient Origins

Ancient DNA analyses began almost forty years ago with the technological advances associated with PCR, or polymerase chain reaction testing, which amplifies DNA sequencing, and were immediately applied to questions about human population history.

Using ancient DNA data helps researchers address questions in anthropology, evolutionary biology, and the environmental and archaeological sciences. This genetic tool has revealed a considerably more dynamic past than was previously appreciated and has revolutionized our understanding of many major prehistoric events.

New understanding of ancient species

The time range for DNA analysis extends to more than half a million years (560,000–780,000 years ago), and many extinct species have now had their genomes completely sequenced, including woolly mammoths and cave bears, as well as human populations from Vikings to Neandertals. It has also allowed researchers to identify new branches of the human family tree with minimal fossil evidence, like the close relatives of Neandertals—the Denisovans—as well as the floral and faunal resources used by these people from bone and tooth fragments, soils, and shells.

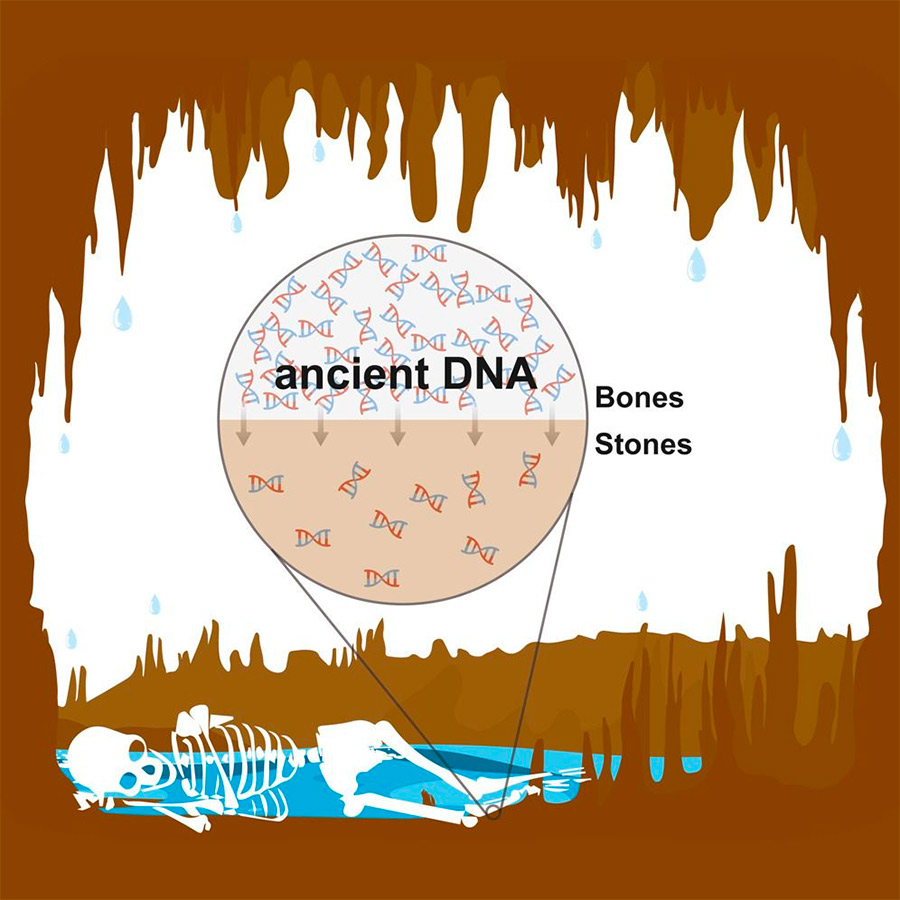

Ancient DNA diffuses from human bones to cave stones.

Image credit Shutterstock

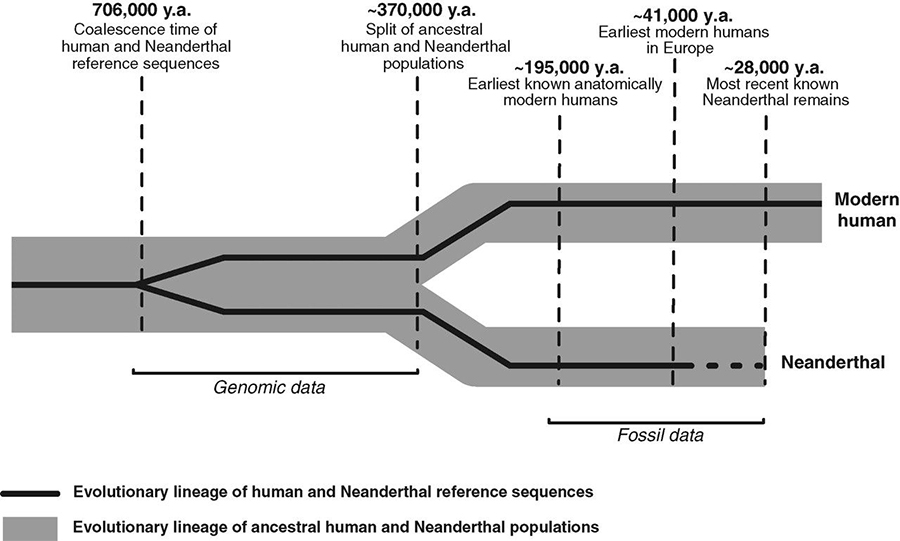

The first Neandertal mitochondrial DNA was recovered in 1997, and the first genome sequenced in 2010. Since then, ancient DNA has provided many surprising insights into human evolutionary history. Among these are the discoveries of the multiple admixture events among late Pleistocene (129,000 to 11,700 years ago) humans and the remnants of archaic DNA in our own genomes. We even see evidence of admixture—when individuals from two or more previously isolated populations interbreed—between early anatomically modern humans and Neandertals prior to the major expansion of anatomically modern humans out of Africa approximately 70,000 to 50,000 years ago. This likely occurred during a climatic period when the Sahara was greener (roughly 120,000 years ago), facilitating interactions in the Middle East.

Divergence estimates for human and Neandertal genomic sequences and ancestral human and Neandertal populations, shown relative to dates of critical events in modern human and Neandertal evolution. <br>Image credit: Science.org

In addition to providing insight into the timing and number of admixture events, the genome data also make it possible to examine population variation and adaptation. From the relatively limited amount of variation found in Archaic humans, we can infer that they had small population sizes with evidence of inbreeding.

Do you have Neandertal DNA?

We can also compare the genomes of modern humans today to see how much DNA has been inherited from archaic humans. Doing this, shows us that non-Africans have about 1.0 to 5.0% archaic human ancestry, which is from Neandertals and Denisovans, and that the ancestry and geographical distribution is not even. For example, people in islands in Southeast Asia and Australia have more Denisovan ancestry than Europeans. Some of the archaic alleles (one or more versions of a DNA sequence) are adaptive, and examples have included alleles related to immunity, skin pigmentation, and high-altitude adaptation.

Using ancient DNA data helps researchers address questions in anthropology, evolutionary biology, and the environmental and archaeological sciences.

Image credit Shutterstock

In addition, in concert with archaeological and paleopathological data, genetic research may shed light on the lives of people in the past including social and societal transformations, diet, environments, mobility, medicines, and health.

Written by Anne Stone PhD