- Paleoecology studies the plants and animals that existed at the same time as hominins, whose fossil bones are studied to help us understand our earliest origins on Earth

- Paleoecology studies complement other research on hominin adaptations and on ancient climates

- Hominins shared a landscape with many other animal species that we also have fossils of

- Functional morphology, or form and structure, lets researchers study the behavior of fossil animals from their bones and teeth

Highlights

Ecology is the study of ecosystems—the plants, animals, and other organisms living together in an environment. Paleoecology extends this into the past to examine and reconstruct ancient ecosystems using the fossils left behind.

Although researchers often like to focus on the evolution of our hominin ancestors, we also know early hominins weren’t alone on the landscape. Studying the other types of fossils found at hominin sites can provide additional insights into how they lived and evolved over time.

From the ground up: Locomotor behavior and habitat preferences

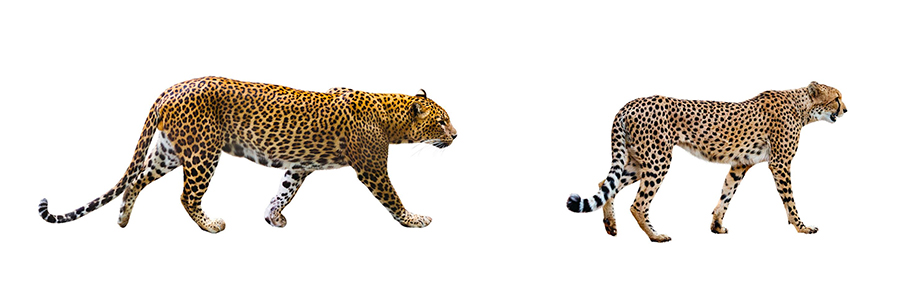

To understand how species were interacting with each other and their environments, paleoecologists first need to reconstruct the behavior of fossil species. The study of functional morphology refers to the relationship between the shape and structure of features like teeth and bones to how animals use those features. For example, researchers studying the functional morphology of hominin feet, knees, and hip bones have been able to determine which fossil species were adapted to living in trees and which were bipedal. By looking at how modern animals behave and what their bones look like, we can then go back to the fossil record and reconstruct the behaviors of their ancient relatives. Did a fossil carnivore have long legs for running fast on an open grassland like a cheetah or powerful muscles to climb trees like a leopard?

Leopard (left) versus cheetah (right). Image credit Shutterstock

Was an antelope better at running straight and fast to escape a predator out on the savanna or zig-zagging side-to-side to try and lose a predator in the forest?

African springbok antelope. Image credit Shutterstock

From the top down: Diet and habitat preferences

Locomotion is just one type of behavior that we can reconstruct in the fossil record. Another common focus of paleoecological studies are animals’ diets, including hominin diets. There are many ways of reconstructing diets in the fossil record. Chemical isotopes in teeth can show if an animal was eating grasses or tree products (like leaves or fruit). Microwear studies of teeth (looking at teeth through a microscope to see tiny marks in the form of grooves and scratches) focus on the structure of foods—if they were tough and fibrous (like leaves) or hard (like seeds). But we can also use functional morphology of the teeth and skulls to look at diet, similar to how we can study locomotion. For example, animals that eat lots of grass (like horses and some antelopes) have powerful jaws for chewing and tall teeth with room to get worn down by all that chewing. But monkeys that eat a lot of soft fruits don’t need powerful jaws or tall teeth.

Zebra teeth and monkey teeth. Image credit Shutterstock

This information about animal diets in the fossil record can also tell us something about the habitats they lived in. An animal that eats lots of grass needs to live near a grassland. An animal eating lots of fruit or leaves would need to live near trees that produce fruit and leaves.

Bringing it all together

Paleoecological studies can focus on re-creating the behavior of just one or two species or they can look at an entire community of fossil animals. When trying to reconstruct the environments of our hominin ancestors, one or two species won’t be much use. Consider this example table of six fossil species that we might find at a hominin site:

| Locomotion—Habitat | Diet | |

|---|---|---|

| Fossil carnivore | Forest | Meat |

| Fossil monkey | Forest | Fruit |

| Fossil giraffe | Forest | Leaves |

| Fossil antelope | Grassland | Grass |

| Fossil pig | Grassland | Grass |

| Fossil hippo | River/Lake | Grass |

If we only focus on the carnivore, monkey, and giraffe, we might think the hominin was living in a closed forest with lots of trees nearby to provide fruit and leaves. If we only focus on the antelope, pig, and hippo, we might think the hominin lived in an open savanna near a river or lake, with only grass to eat. By combining all of the fossil species and their adaptations, we can see instead that this hominin lived somewhere that had a mixed habitat—maybe an open grassland with a small patch of forest growing next to water. Adding more animals and their adaptations will provide even more details about this environment.

Studying the other types of animals found with fossil hominins can provide important details about the habitats they lived in. Results from paleoecological studies match well with what we know about hominin adaptations and paleoclimate information. For example, the site of Aramis in Ethiopia has many arboreal monkeys and leaf-eating antelopes that we would expect to find in a forest habitat. So it’s not surprising that Ardipithecus ramidus, found at that site, still has an opposable big toe for moving around in the trees! At sites where we don’t yet have evidence of hominin adaptations, paleoecology can help researchers form hypotheses about what those hominins were doing. And when we do find evidence of hominin behavior, paleoecology can help confirm these results.

Written by Irene Smail PhD