- The Last Glacial Maximum at around 21,000 years ago affected people and places around the world

- Evidence of the effect on early modern humans in South Africa shows the adaptability of humans to climate and environmental changes

- Coastal resources were important but the usage of plant and interior resources is also evident at Waterfall Bluff, South Africa between 35,000 and 10,000 years ago.

Highlights

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) was the period around 21,000 years ago of maximum global ice volume along with a pronounced cooling over most of the globe. It affected people and places around the world and led to the formation of the Sahara Desert and caused major reductions in Amazonian rainforest. In Siberia, the expansion of polar ice caps led to drops in global sea levels, creating a land bridge that allowed people to cross into North America.

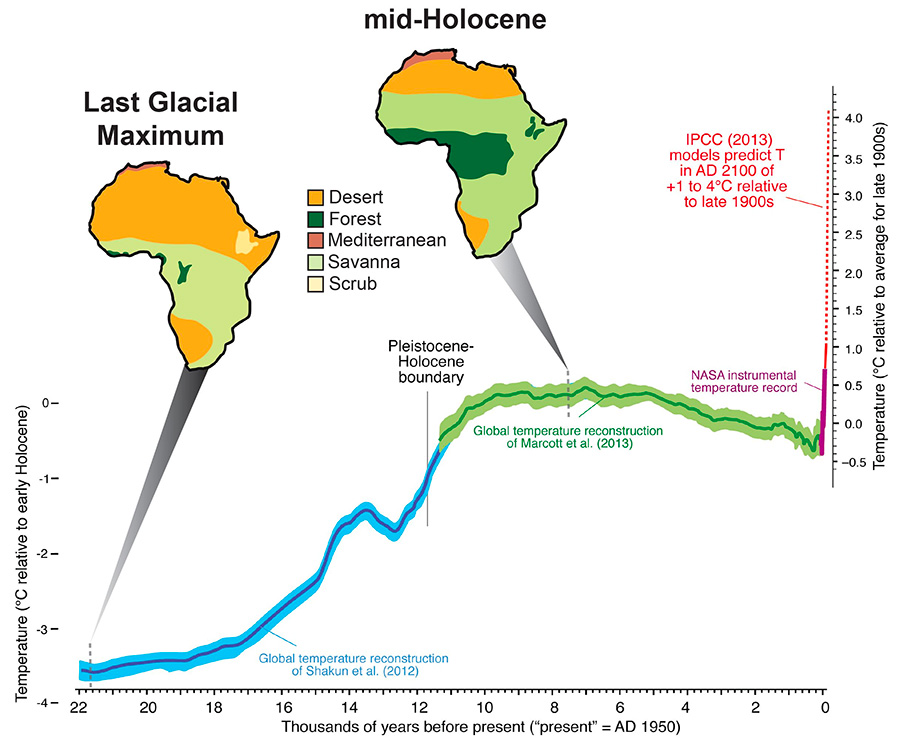

Temperature, vegetation and human population growth changes over the last 22,000 years. The cool and arid Last Glacial Maximum saw the expansion of desert environments at the expense of forests, whereas the warm and wet mid-Holocene was characterized by an expansion of savannas and forests. These environmental changes greatly influenced the distribution of African mammal communities. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projects up to 4°C increase by 2100 and the United Nations (UN) projects human population growth to exceed 11 million people by then.

Rowan et al October 2016, Proceedings of the Royal Society B https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2016.1207 (Image modified with permission from Railsbeck's “Fundamentals of Quaternary Science” http://www.gly.uga.edu/railsback/FQS/FQS.html)

Evidence of human occupation on the coast

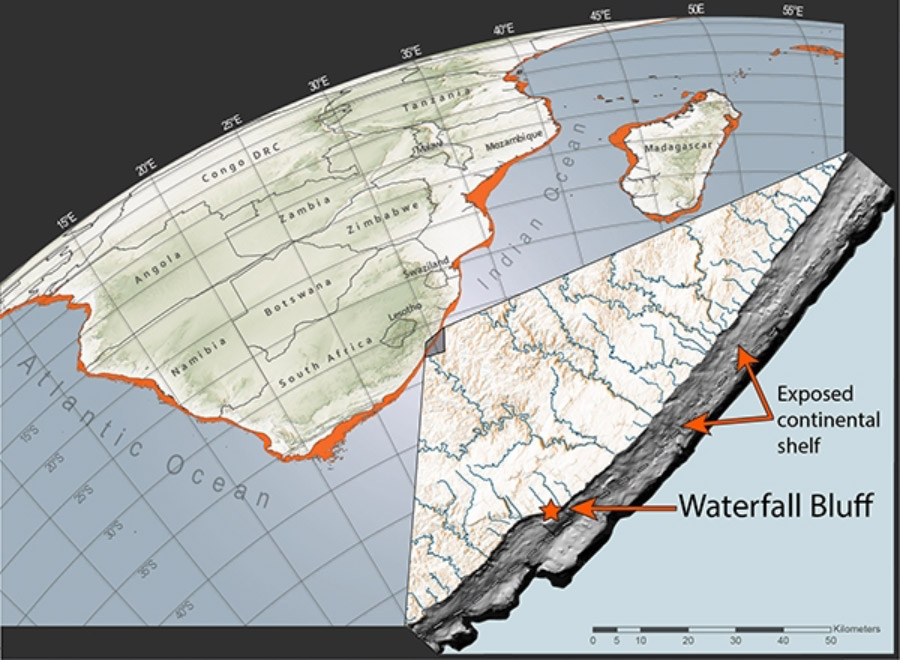

In southern Africa, archaeological records from this globally cold and dry time are rare because there were widespread movements of people as they abandoned increasingly inhospitable regions. Yet records of coastal occupation and foraging in southern Africa are even rarer. The drops in sea level during the Last Glacial Maximum and earlier glacial periods exposed an area on the continental shelf across southern Africa, especially along the coast in southwestern Africa, nearly as large as the island of Ireland. Hunter-gatherers wanting to remain near coastlines during these times had to trek out onto the exposed continental shelf. Yet these records are gone now, either destroyed by rising sea levels during warmer interglacial periods or submerged under the sea.

Two views from a cave opening on the South African coast—left—200,000 years ago when lowered sea levels during glacial phases expose the vast Palaeo-Agulhas Plain, and right—today, covered by the Indian Ocean.

Image credit Erich Fisher

Humans have a long-standing relationship with the sea that spans nearly 200,000 years. Researchers have long hypothesized that places like coastlines helped people mediate global shifts between glacial and interglacial conditions and the impact that these changes had on local environments and resources needed for their survival. Coastlines were so important to early humans that they may have even provided key routes for the dispersal of people out of Africa and across the world.

Research documents a persistent human occupation along the South African eastern seaboard from 35,000 years ago to 10,000 years ago. In this remote, and largely unstudied, location—known as the “Wild Coast”—researchers have used a suite of cutting-edge techniques to reconstruct what life was like during this inclement time and how people survived it.

Mpondoland study area

The scientists studied coastal adaptations, diets, and mobility of hunter-gatherers across glacial and interglacial phases of the Quaternary period in coastal South Africa with excavations at the Mpondoland coastal rock shelter site known as Waterfall Bluff. These excavations have uncovered evidence of human occupations from the end of the last ice age, approximately 35,000 years ago, through the complex transition to the modern time, known as the Holocene. Importantly, these researchers also found human occupations from the Last Glacial Maximum, which lasted from 26,000 to 19,000 years ago.

Mpondoland study area showing a thin continental shelf area.

Image credit Erich Fisher

Persistent human occupation

In Mpondoland, a short section of the continental shelf is only 10 kilometers wide. That distance is less than how far we know past people often traveled in a day to get sea foods, meaning that no matter how much the sea levels dropped anytime in the past, the coastline was always accessible from the archaeological sites that have been found on the modern Mpondoland coastline.

One of the highest-resolution chronologies, or layers of archaeological remains, showing persistent human occupation and coastal resource use is at Waterfall Bluff from 35,000 years ago to 10,000 years ago. There, researchers are documenting the first direct evidence of coastal foraging in Africa during a glacial maximum and across a glacial/interglacial transition. The oldest record of coastal foraging, which has also been found in southern Africa, shows that people relied on coastlines for food, water, and more favorable living conditions over tens of thousands of years. Interestingly, scientists think it may have been the centralized location between land and sea and their plant and animal resources that attracted people and supported them amid repeated climatic and environmental variability.

The evidence, in the form of marine fish and shellfish remains, shows that prehistoric people repeatedly sought out dense and predictable seafoods. Other research has looked at the interactions between prehistoric people’s plant-gathering strategies and climate and environmental changes over the last glacial/interglacial phase. This research combines preserved plant pollen, plant phytoliths, macro botanical remains (charcoal and plant fragments) and plant wax carbon and hydrogen isotopes from the same archaeological archive and allowed researchers to study interactions between hunter-gatherer plant-gathering strategies and environmental changes across a glacial-interglacial transition.

Waterfall Bluff, South Africa.

Image by Erich Fisher.

This research shows that people who lived at Waterfall Bluff collected wood from coastal vegetation communities during both glacial and interglacial phases. It is another link to the coastline for the people living at Waterfall Bluff during the Last Glacial Maximum. The exceptional quality of the archaeological and paleoenvironmental records at Waterfall Bluff demonstrates that those hunter-gatherers targeted different, but specific, coastal ecological niches, all while collecting terrestrial plant and animal resources from throughout the broader landscape and maintaining links to highland locales inland. This research enriches our understanding about the adaptive strategies of people facing widespread climatic and environmental changes.

Written by Erich Fisher PhD

Read more about “How many ice ages has the Earth had, and could humans live through one?” written by Denise Su and published online at The Conversation.