- Life history is defined by the growth, developmental, and reproductive events that occur over the course of one’s life

- Each species has a unique life history that is linked to other biological traits such as brain size and energy availability

Highlights

One important aspect of human biology and evolution is understanding life history. An individual’s or species’ “life history” is defined by the timing and duration of growth, developmental, and reproductive events that occur throughout the course of one’s life. These events include birth, weaning (the process through which infants cease to be reliant on their mothers’ milk), periods of rapid and slow growth, reproduction, and death.

Maximizing reproductive fitness

When these events occur and how long different stages of life last vary from species to species. This is because a species’ life history evolved to allocate available energy growth, body maintenance, and reproduction in a way that will maximize reproductive fitness (the name of the game in evolution) given the species’ ecological conditions.

Energy comes from the food an animal consumes and is a finite resource, so scientists often think of life history strategies in the context of “trade-offs.” For example, some organisms, like rabbits, have short lifespans, begin reproducing early in life, and produce many offspring at once. Others, like modern humans, have long lifespans, begin reproducing comparatively late, and most often give birth to singletons. Humans, therefore, can invest more energy and resources into their few offspring than rabbits can in their many, but run the risk of dying before they have children. Humans must also invest heavily in their offspring to ensure that they survive, while rabbits can provide comparatively little parental care and still count on a few of their many offspring making it to adulthood.

Rabbits produce many offspring to help ensure its survival against predators and environmental conditions.

Image credit Shutterstock

Large, expensive brains

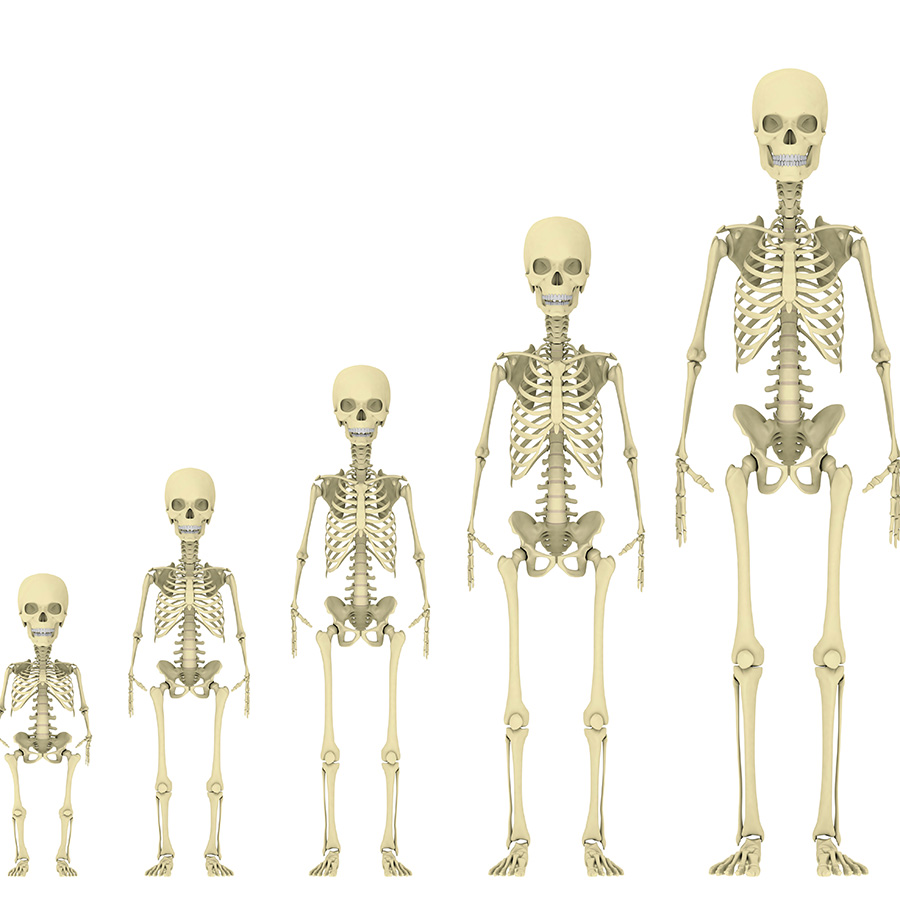

Many of the life history traits that we see in modern humans are linked to ensuring that our offspring do survive until adulthood so that they have the chance to reproduce. Compared to many other mammals, modern humans wean early and have an extended growth period characterized by an adolescent growth spurt (the cause of many a pair of outgrown jeans!). We also begin reproducing late, have shorter than expected interbirth intervals, and have a long post-reproductive lifespan. Although brain size is not a life history trait, brain size is also linked to life history, and modern humans have large, energetically expensive brains that require a long developmental period.

Human life history is defined by the growth, developmental, and reproductive events that occur over the course of one’s life.

Image credit Shutterstock

These traits are all interrelated and together allow modern humans to grow successfully into independent adults while providing sufficient time and energy for the development of our bodies, brains, skills, and social connections. Anyone who’s spent time around a human infant or toddler knows how much human children have to learn before reaching maturity. Slow childhood growth allows humans to buffer against potential energy shortages, divert energy towards a developing brain, and provides ample time to acquire complex skills, which means that young humans require many years of care.

Early weaning, however, allows human mothers to have more than one dependent offspring at the same time, so humans rely on other members of their family or social group to help with the care of younger offspring. These helpers are often adults who have no dependent offspring themselves (such as grandparents) or older siblings.

As children grow from infant to older child, their supervision can be delegated for short periods to an older sibling or caregiver, freeing the parents to take care of other responsibilities.

Image credit Shutterstock

A developing growth story

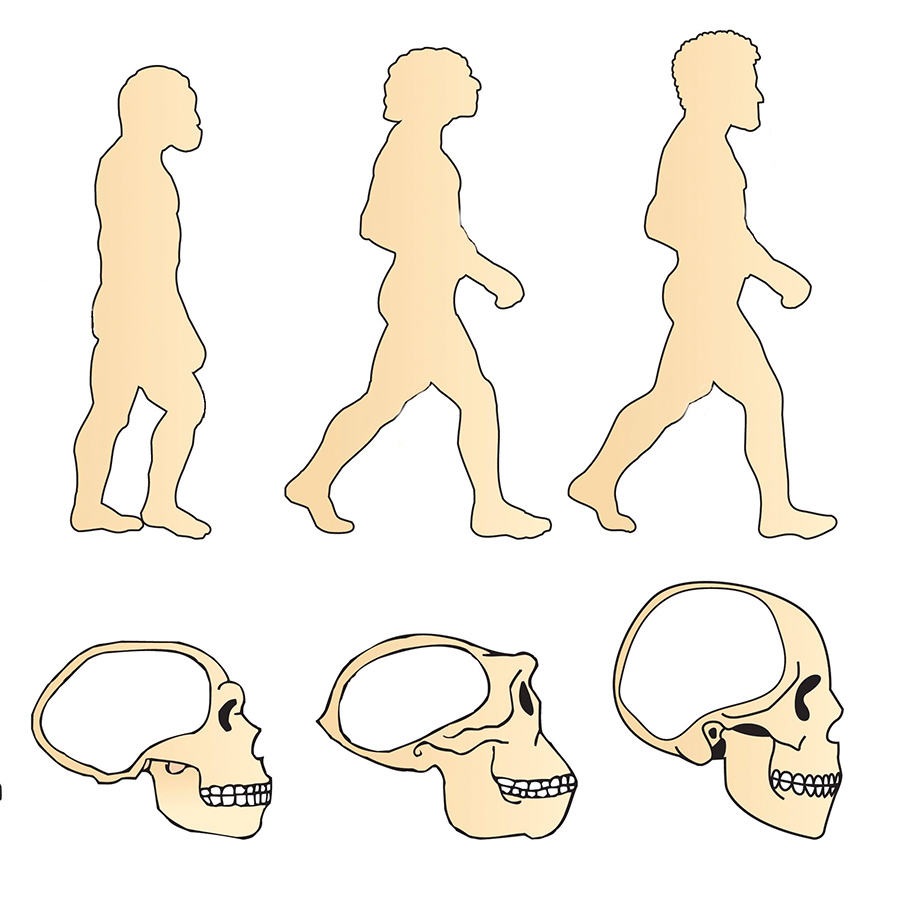

Life history traits can be tricky to study in the fossil record, but scientists often use the correlation between the timing of dental development and overall pace of life history in living primates to make predictions about fossil hominins. Most evidence suggests that the combination of traits we see in modern humans is unique to our species.

Every past hominin species has a unique life history that is linked to other biological traits such as brain size and energy availability.

Image credit Shutterstock

Early hominins, such as Australopithecus species, almost certainly had life histories more similar to living chimpanzees than to modern humans. But even Homo erectus, who was much more human-like in body proportions and size than earlier hominins, still seems to be more similar to modern great apes in its growth and development. New technologies that utilize isotope signatures in teeth are helping scientists study weaning patterns in extinct hominins such as Neandertals, so these and other technological advances are sure to expand researchers’ understanding of life history in the hominin fossil record.

Written by Amanda McGrosky PhD