- Mt. Toba’s eruption 74,000 years ago severely impacted life on Earth, but research at the tip of South Africa shows that humans continued to thrive despite a global “winter.”

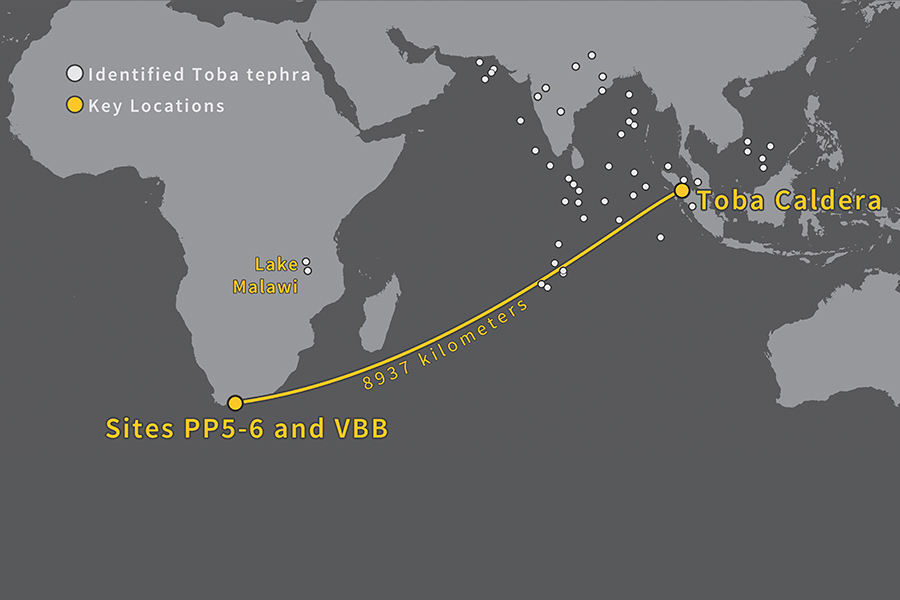

- Ash from super-volcanic eruptions, like Mt. Toba, were disbursed around the globe.

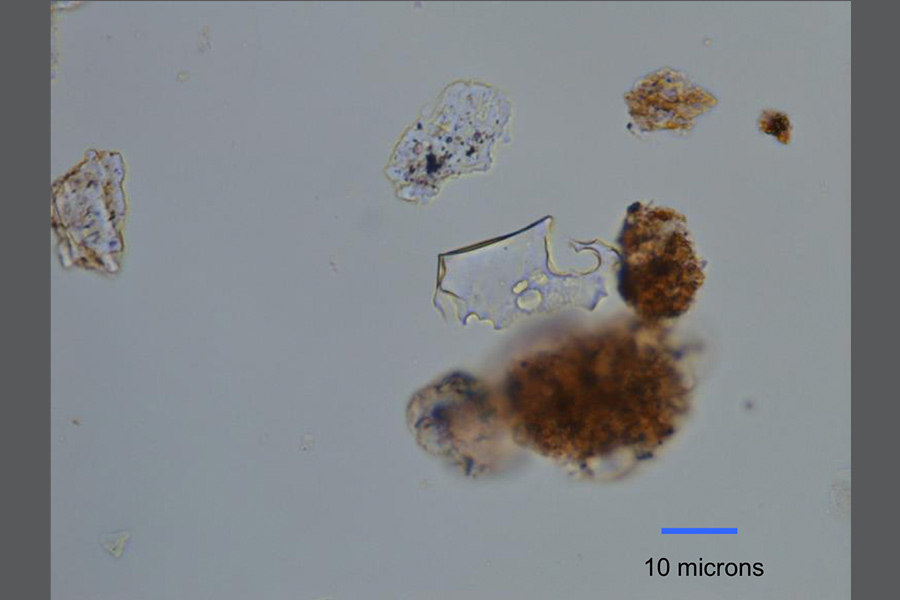

- Volcanic “shards” or microscopic glass particles have a particular “signature” for each volcano and so can be identified in sediments far removed from the volcano’s location.

- This research also allowed scientists to pinpoint, with new accuracy, the exact dates of sediments at Pinnacle Point, South Africa, which also confirms the accuracy of OSL dating.

Highlights

Imagine a year in Africa when summer never arrives. The sky takes on a gray hue during the day and glows red at night. Flowers do not bloom. Trees die in the winter. Large mammals like antelope become thin, starve, and provide little fat to the predators (carnivores and human hunters) that depend on them. Then, this same disheartening cycle repeats itself, year after year.

This is a picture of life on earth after the eruption of super-volcano Mount Toba in Indonesia about 74,000 years ago. Through these conditions though, scientists believe that early modern humans on the coast of South Africa thrived through this event.

Volcanic eruption with intense dust and debris thrown into the atmosphere.

Image credit Shutterstock

Life after a mega-eruption

The effect of the Toba eruption would have certainly impacted some ecosystems more than others, possibly creating areas, or refugia, in which some human groups did better than others throughout the event. Whether or not your group lived in such a refuge would have largely depended on the type of resources available.

Researchers have been studying an archaeological site at the southern tip of South Africa where there is evidence of this kind of human refuge during glacial periods, from around 195,000 to 130,000 years ago and again between 74,000 and 60,000 years ago. Coastal resources, like shellfish, were highly nutritious and less susceptible to the eruption than the plants and animals of inland areas.

An eruption a hundred times smaller than Mount Toba—that of Mount Tambora, also in Indonesia, in 1815—is thought to have been responsible for a year without summer in 1816. The impact on the human population was dire—crop failures in Eurasia and North America, famine, and mass migrations. The effect of Mount Toba, a super-volcano that dwarfs even the massive Yellowstone eruptions of the deeper past, would have had a much larger, and longer-felt, impact on people around the globe.

The shards at Pinnacle Point were carried nearly 9000 km from the source in Indonesia.

Image credit Erich Fisher

Years long “volcanic” winter

The scale of the ash-fall alone attests to the magnitude of the environmental disaster. Huge quantities of aerosols injected high into the atmosphere would have severely diminished sunlight—with estimates ranging from a 25 to 90% reduction in light. Under these conditions, plant die-off is predictable, and there is evidence of significant drying, wildfires and plant community change in East Africa just after the Toba eruption.

If Mount Tambora created such devastation over a full year—and Tambora was a hiccup compared to Toba—we can imagine a worldwide catastrophe with the Toba eruption, an event lasting several years and pushing life to the brink of extinction.

Ash and volcanic shards

When the column of fire, smoke, and debris blasted out the top of Mount Toba, it spewed rock, gas, and tiny microscopic pieces (cryptotephra) of glass that, under a microscope, have a characteristic hook shape produced when the glass fractures across a bubble. Pumped into the atmosphere, these invisible fragments spread across the world.

A volcanic glass shard erupted 74,000 years ago from the Toba volcano in Indonesia found at an archaeological site nearly 9000 km away at Vleesbaai, South Africa.

Image credit Rachael Johnsen

Researchers saw the potential of finding the Toba shards in the sediments of a South African archaeological site. Their investigations revealed a single shard of this explosion under a microscope in a slice of archaeological sediment encased in resin. The shard came from an archaeological site in a rockshelter called Pinnacle Point 5-6, on the south coast of South Africa near the town of Mossel Bay. The sediments dated to about 74,000 years ago. Encased in that shard of volcanic glass is a distinct chemical signature, a fingerprint that scientists can use to trace to the killer eruption.

Scientists and students digging at Vleesbaai, South Africa, where volcanic shards from the Mt. Toba eruption were found.

Image credit Curtis Marean

A continuously inhabited site

Most studies have looked at whether or not Toba caused environmental change. It did, but such studies lack the archaeological data needed to show how Toba affected humans. The research team was also documenting a continuous human occupation at Pinnacle Point across the volcanic event. Many previous studies had tried to test the hypothesis that Toba devastated human populations, but these failed because they were unable to present definitive evidence linking a human occupation to the exact moment of the event.

The sample locations at Pinnacle Point and Vlessbai, representing stone artifacts, bone, and other cultural remains of the ancient inhabitants, were used to build digital models of the site. The models tell us a lot about how people lived at the site and how their activities changed through time. What researchers found was that during and after the time of the Toba eruption people lived at the site continuously, and there was no evidence that it impacted their daily lives.

Confirming the accuracy of OSL dating techniques

In addition to understanding how Toba affected humans in this region, this research has other important implications for archaeological dating techniques. Archaeological dates at these age ranges are imprecise—10% (or thousands of years) error is typical. Toba ash-fall, however, was a very quick event that has been precisely dated. The time of shard deposition was likely about two weeks in duration—instantaneous in geological terms.

This research found shards at two sites—the Pinnacle Point rockshelter (where people lived, ate, worked and slept) and an open-air site about 10 kilometers away called Vleesbaai. This latter site is where a group of people, possibly members of the same group as those at Pinnacle Point, sat in a small circle and made stone tools. Finding the shards at both sites allows researchers to link these two records at almost the same moment in time.

Not only that, but the shard location allows the scientists to provide an independent test of the age of the site estimated by other techniques. People lived at the Pinnacle Point 5-6 site from 90,000 to 50,000 years ago.

Not far from Vleesbai is Pinnacle Point, South Africa, where archaeological materials found in cave sites have confirmed early modern human habitation from 250,000 to 50,000 years ago—during the time of the Mt. Toba eruption.

Image credit Erich Fisher

Optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) was used to date 90 samples and develop a model of the age of all the layers. OSL dates the last time individual sand grains were exposed to light. There has been some debate over the accuracy of OSL dating, but the model dated the layers where the Toba shards were found to about 74,000 years ago—right on the money.

This lends very strong support to a cutting-edge approach to OSL dating, which has been applied to sites across southern Africa and the world.

Human survival in a coastal environment

In the 1990s, scientists began arguing that this eruption of Mount Toba, the most powerful in the last two million years, caused a long-lived volcanic winter that may have devastated the ecosystems of the world and caused widespread population crashes, perhaps even a near-extinction event in our own lineage, a so-called bottleneck.

This research shows that along the food-rich coastline of southern Africa, people thrived through this mega-eruption, perhaps because of the uniquely rich food regime on this coastline. Now other research teams can take the new and advanced methods developed in this study and apply them to their sites elsewhere in Africa so researchers can see how these devastating times affected other populations.

Written by Curtis Marean PhD