Fossils attributed to Australopithecus anamensis (which means “southern ape of the lake,” from “anam” or lake in the Turkana language) have been recovered from sites in the Turkana Basin in Kenya (Allia Bay and Kanapoi) as well as in Ethiopia (Middle Awash and Woranso-Mille). These fossils, which have been dated to between 4.2 and 3.8 million years ago, using radioisotopic dating methods applied to volcanic sediments, are significant because they represent the earliest indisputable evidence of obligate bipedality in the human fossil record. In addition, the morphology of the skull of Au. anamensis provides a glimpse of the evolutionary changes that represent the transition from earlier, more primitive (i.e., ape-like) hominins—such as Ardipithecus ramidus—to later, more derived (i.e., human-like) species—such as Australopithecus afarensis.

Although Au. anamensis is represented by both cranial and postcranial remains (i.e., from the parts of the skeleton below the head), cranial and dental fossils outnumber those of the limbs and trunk. Au. anamensis possesses some features in the dentition— relatively large, broad premolars and molars with relatively thick tooth enamel—that are shared with other species in the genus Australopithecus and early fossil representatives of the genus Homo. Other features found in the teeth of Au. anamensis, however, differ from those found in later species in the genus Australopithecus and more closely resemble the condition found in living apes. These features include the size of the incisors (the flat, broad teeth in the front of the jaws), which are wider than in later australopiths (species in the genera Australopithecus and Paranthropus); the size and shape of the lower third premolar, which is larger and single-cusped, unlike the smaller and double-cusped condition found in later australopiths; the shape of the upper canine, which is symmetrical when viewed from the side, unlike the asymmetrical profile found in later australopiths; and the shape of the first deciduous (milk) molar, which, unlike later australopiths, does not closely resemble a permanent molar. Canine size is smaller in Au. anamensis than in the genus Ardipithecus, but these teeth (especially their roots) are larger than in Au. afarensis.

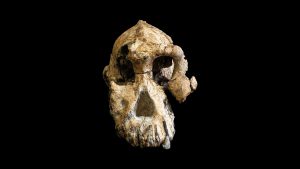

The skull of Au. anamensis was only represented by fossils of the mandible (lower jaw), maxilla (the bone that comprises the upper jaw and most of the face), a single temporal bone (the bone that surrounds the ear and forms part of the side of the skull), and isolated teeth. Consequently, little was known about the overall appearance of the face until the recent discovery of the MRD-VP-1/1 cranium from the site Woranso-Mille in Ethiopia. Like the teeth, these skull fossils bear many primitive, ape-like features. The dental arcade is narrow and slightly U-shaped when viewed from above, with the molars and premolars located directly behind the canines. This ape-like shape contrasts with the more parabolic-shaped dental arcade found in Au. afarensis and later hominins. The mandibular symphysis (the bony region where the left and right halves of the mandible meet) is more ape-like in shape. When looking at a cross-section of this region, the symphysis is heavily angled compared to later hominins. In Au. afarensis, for example, this region of the mandible is more vertically oriented. Due to the large size of the upper canine roots (see above), the margins of the nasal opening are rounded; in Au. afarensis, the lower margins are sharper. Finally, similar to that found in living apes, the bony ear opening in Au. anamensis is relatively small.

The postcranial elements of Au. anamensis include fossils of the hindlimb and forelimb, including portions of the wrist and hand. The fossil tibiae (plural of tibia-shin bone) are of particular importance because they demonstrate that this species walked bipedally. Both the knee- and ankle-ends of the tibia (shin bone) are thickened, and the tibial plateau, where the tibia connects to the femur (thigh bone), is larger than in living apes. These features demonstrate that Au. anamensis was a biped because they indicate that more weight was borne on the tibia, a feature requisite for bipedality. The single wrist bone of Au. anamensis suggests that this species had limited wrist rotation, more similar to extant apes than to later australopiths and species in the genus Homo, who have a greater range of motion in this joint. Finally, estimates of body size suggest that, at roughly 47-55 kilograms (100-120 pounds), Au. anamensis was slightly larger than Au. afarensis and Ar. ramidus, and sexual dimorphism (i.e., size and shape differences between males and females of the species) was like that found in Au. afarensis.

The evolutionary relationship between Au. anamensis and Au. afarensis has received a great deal of scholarly interest. The fossils of Au. anamensis from Kanapoi are geologically older than those from Allia Bay and are more plesiomorphic (primitive) than the Au. anamensis sample from Allia Bay. The Allia Bay Au. anamensis sample is more similar to the older sample of Au. afarensis fossils found at Laetoli, Tanzania, than they are to the younger sample of Au. afarensis fossils from Hadar, Ethiopia. These facts have led some researchers to suggest that Au. anamensis is the direct ancestor of Au. afarensis and the sequence of fossils from Kanapoi, Allia Bay, Laetoli, and Hadar can be considered a single evolving species lineage. The trends suggesting that this sequence of fossils represents a single species come predominantly from the size and shape of the mandible and lower third premolar. For clarity and to formalize the differences found in this single species, which would include fossils currently assigned to Au. afarensis and Au. anamensis, however, most scholars continue to regard the fossils as separate species.

The environments in which Au. anamensis lived have generally been reconstructed as mosaic, heterogenous environments composed of woodland, bushland, and grassland habitats near lakes and/or rivers. However, there is notable variation between the environments of the different sites where Au. anamensis fossils have been found. Combined with evidence from other early purportedly bipedal hominin species (e.g., Ardipithecus kadabba and Ar. ramidus), these environmental reconstructions argue strongly against the once wide-held idea that bipedalism initially evolved and flourished in open savanna environments.